Figure 5: Breakdown of cybercrime reports by jurisdiction for FY2023-24

Note: Approximately one per cent of reports came from anonymous reporters and other Australian territories. Data has been extracted from live datasets of cybercrime and cyber security reports reported to ASD. As such, the statistics and conclusions in this report are based on point-in-time analysis and assessment.

In FY2023-24, the total self-reported BEC losses to ReportCyber were almost $84 million. There were over 1,400 reports of BEC made to law enforcement through ReportCyber that led to a financial loss. On average, the financial loss from each confirmed BEC incident was over $55,000. Most confirmed BEC reports came from Queensland (434 reports).

Case study 7: Medibank and LockBit Cyber sanctions

In January 2024, under the Autonomous Sanctions Act 2011 the Australian Government sanctioned Russian national Aleksandr Ermakov for his role in the compromise of the Medibank Private network in 2022. This was the first use of the Australian Government’s autonomous cyber sanctions framework.

Nearly 10 million personal records were stolen during the cyber security incident against Medibank, including names, dates of birth, Medicare numbers, and sensitive medical information. Some records were published on the dark web.

In May 2024, as part of a separate investigation, the Australian Government imposed Australia’s second cyber sanction against Russian national Dmitry Yuryevich Khoroshev, for his senior leadership role in the LockBit ransomware group. LockBit is a prolific cybercriminal ransomware group and works to destabilise and disrupt key sectors for financial gain.

The cyber sanctions imposed by the Australian Government on Ermakov and Khoroshev were targeted financial sanctions and travel bans under the AFP and ASD established Operation AQUILA, together with other Australian government agencies and international partners.

Sanctions are an important part of the Australian Government’s toolkit in countering cybercrime. Cyber sanctions impose cost on cybercriminals’ ability to operate.

- Cyber sanctions reveal the real-world identities of cybercriminals, undermining their credibility.

- For others in the crime ecosystem, affiliating with a sanctioned cybercriminal could be perceived as higher risk.

- Breaching a cyber sanction can be a serious criminal offence, punishable by up to 10 years imprisonment and/or significant financial penalties.

Artificial intelligence is changing the cybercrime landscape

The increasing prevalence of artificial intelligence (AI) means that Australia must be responsive to an ever changing cyber threat landscape. Cybercriminals may leverage AI-enhanced social engineering as it is accessible to low-capability actors and can be used to circumvent network defences. For example, AI will allow cybercriminals to undertake more labour intensive activities, such as generating spear phishing content more efficiently and on a larger scale. Cybercriminals may also use AI to create new methods of social engineering attacks, such as imitating a target’s voice based on an audio sample.

Using AI in social engineering attacks means that cybercriminals can maximise their success rates with little additional effort, increasing the potential for network compromise and the overall threat posed by social engineering.

Case study 8: Vishing – a video phishing scam

In early 2024, media reported a vishing scam involving a multinational corporation where cybercriminals used AI-generated deepfakes during a video conference call to convince an employee to transfer millions of dollars. The employee initially thought it was a phishing scam, after receiving a message purporting to be the company’s UK-based chief financial officer. However, after attending a video conference call and recognising other colleagues in attendance, the employee was reassured the request was legitimate and completed the financial transaction. All attendees at the conference call, except the employee, were deepfake recreations.

Although AI is used by cybercriminals, other applications for AI in cyber security are likely to emerge, including combatting cybercrime. For example, AI can enhance the detection and triage of cyber security incidents and identify malicious emails and phishing campaigns, making them easier to counteract.

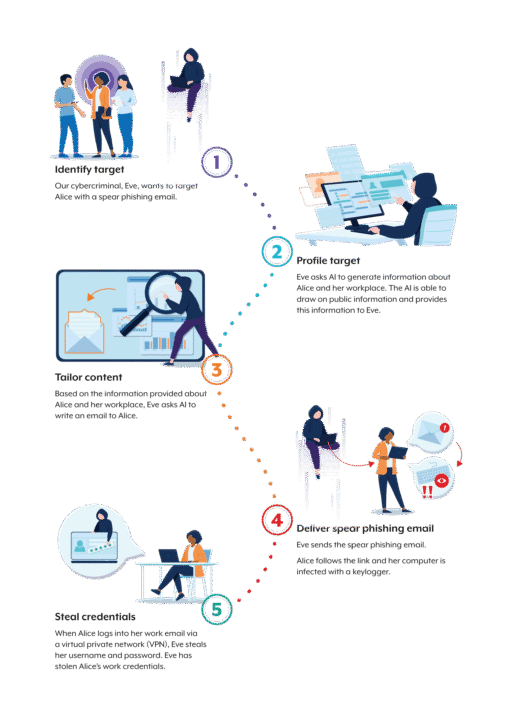

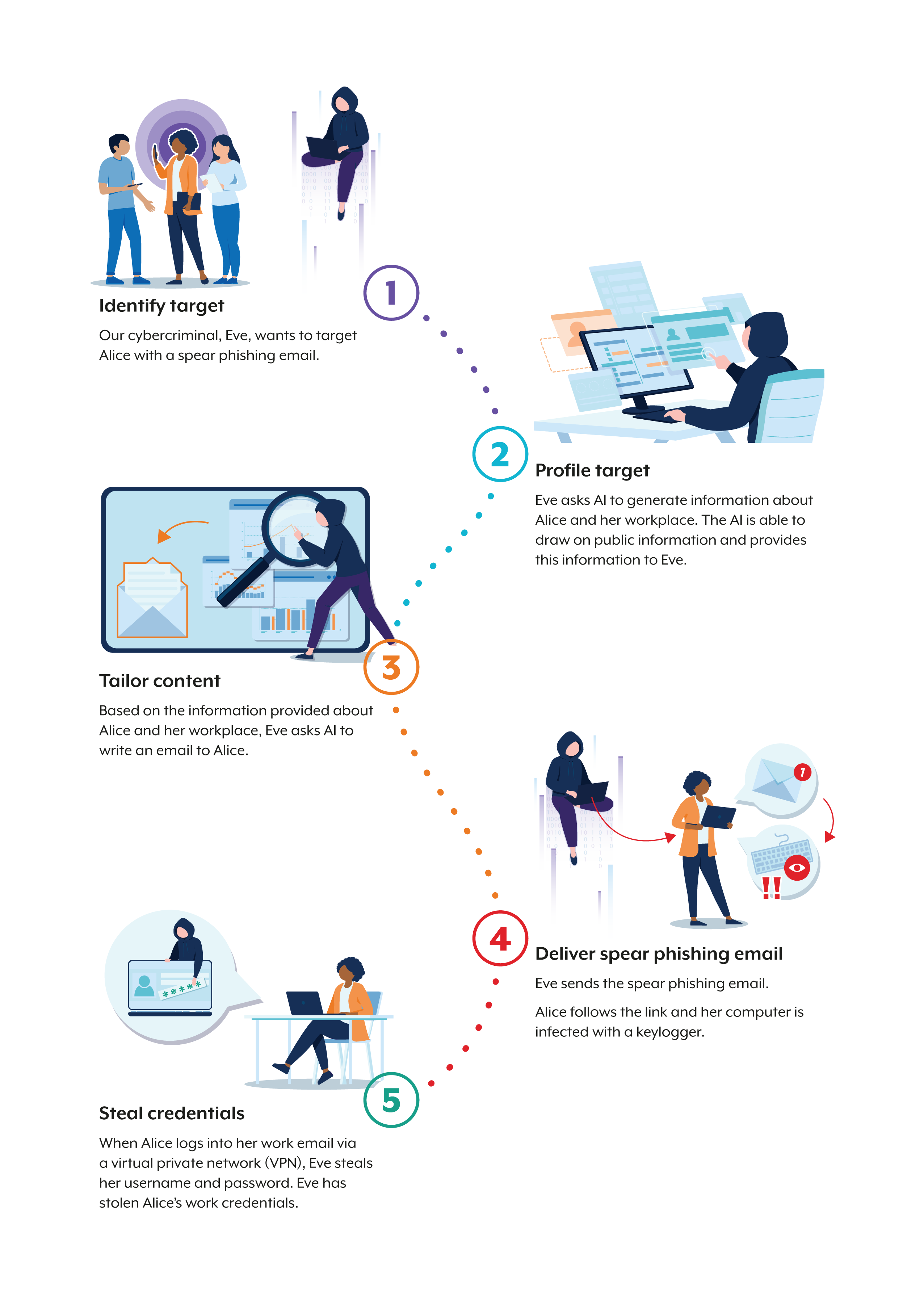

Hypothetical cybercriminal using AI-enabled social engineering

- Identify target: Our cybercriminal, Eve, wants to target Alice with a spear phishing email.

- Profile target: Eve asks AI to generate information about Alice and her workplace. The AI is able to draw on public information and provides this information to Eve.

- Tailor content: Based on the information provided about Alice and her workplace, Eve asks AI to write an email to Alice.

- Deliver spear phishing email: Eve sends the spear phishing email. Alice follows the link and her computer is infected with a keylogger.

- Steal credentials: When Alice logs into her work email via a virtual private network (VPN), Eve steals her username and password. Eve has stolen Alice’s work credentials.

Ransomware is persistent and pervasive

Ransomware continues to pose significant operational, financial and reputational risk to Australia. Ransomware is a type of extortion that uses malware to encrypt data or systems. In FY2023–24, ASD responded to 121 ransomware incidents – accounting for around 11% of all reported incidents. More recently, malicious cyber actors have adjusted their tactics to include stealing sensitive data. Malicious cyber actors then extort payments from victims in return for the recovery of, and ability to regain access to, encrypted data. According to the Australian Institute of Criminology’s (AIC) Cybercrime in Australia 2023 report, 12% of ransomware victims were also extorted for payment to prevent their data being leaked or sold online.

Increasingly, cybercriminals are also exfiltrating data without encrypting victim systems, known as data theft extortion. This data is more attainable for less technically skilled actors, and cybercriminals perceive it is just as lucrative as ransomware given the breadth of Australian organisations that hold sensitive data.

Ransomware attacks are highly destructive, causing significant harm to individuals, organisations, and wider society. For example, businesses may experience reputational damage and financial losses from offline systems and data loss. According to the AIC, small to medium businesses are high-risk targets for ransomware attacks, with small to medium business owners (6.2%) being more likely to be the victim of a ransomware attack compared with employees (3.2%) and individuals who were not small to medium business owners or employees (1.5%).

ASD advises against paying extortion demands. Payment does not guarantee that victims’ data is recoverable (even if it is returned) or prevent it from being sold or leaked online. Paying a ransom also encourages the continuation and proliferation of the cybercriminal business model.

Countering ransomware groups

Case study 9: Operation ORCUS

Operation ORCUS is the AFP’s ransomware taskforce representing Australia as part of the Europol-led international law enforcement Operation CRONOS. Operation ORCUS is supported by the Joint Standing Operation between the AFP and ASD: Operation AQUILA. Operation AQUILA leverages the complementary powers, capabilities and intelligence of ASD and the AFP to disrupt the most serious cybercrime threats facing Australia.

In December 2023, under Operation ORCUS–PANTHERA, the AFP participated in a global law enforcement operation against the ALPHV/BlackCat ransomware syndicate – seizing criminal infrastructure and websites. The global operation also developed a decryption tool to help victims recover their data and systems. The AFP identified at least 56 Australian businesses and government agencies that had been targeted by the ransomware group. The AFP engaged with those victims to provide decryption keys and restore systems.

In February 2024, under Operation ORCUS-JUNKERS, the AFP participated in a global law enforcement operation that disrupted the world’s most prolific ransomware group, LockBit, which has caused billions of dollars in harm across the world – including millions in harm to Australian individuals and businesses. The global operation seized criminal infrastructure, including LockBit’s primary platform and 34 servers, more than 200 cryptocurrency accounts, and significant amounts of technical data.

Common techniques used by cybercriminals

Credential stuffing – a growing threat for organisations

Credential stuffing – the use of stolen usernames and passwords to access other services and accounts via automated logins – is one of the most common cyber attacks affecting individuals and businesses. When mounting an attack, malicious cyber actors use stolen login credentials across as many websites as possible. Once logged in, they may be able to access victims’ accounts without the website or real account holder being alerted. Credential stuffing attacks can cause monetary loss for account holders and identity theft depending on the type of accounts breached and the information stored in them.

Customers often save payment details to websites to speed up transactions, meaning when an account is compromised, a customer’s payment details may also be accessed. Victims of credential stuffing are often only made aware of an attack when they are unable to log into their account or when they notice an unauthorised bank transaction and raise it with the business.

According to the AIC’s Cybercrime in Australia 2023 report, 34% of respondents had their financial or personal information exposed in a data breach in the 12 months prior to the survey. Of these, 79% were notified by the company whose data was leaked or by a government or financial agency.

Once a malicious cyber actor’s login attempt is successful, they may then engage in other criminal activity, including:

- making fraudulent purchases using victims’ stored payment details

- selling personal data and compromised accounts online via the dark web

- using stolen data to commit identify theft and/or to further advance phishing campaigns

- conducting an account takeover, where the threat actor locks the victim out of their account and changes security settings, contact details and other personal details.

In December 2023, a US genetic testing company, 23andMe, notified 6.9 million users that a small percentage of accounts had been compromised due to a credential stuffing attack. Information accessed by the threat actor included ancestry and health-related information. In a separate cyber security incident in 2024, customers of an online Australian retailer had their accounts accessed via credential stuffing, and stored payment details were used to fraudulently purchase goods.

Due to the rise in credential stuffing-related data breaches, individuals and organisations have become increasingly at risk of credential stuffing attacks. The effectiveness of credential stuffing attacks is reliant on passwords being reused across multiple accounts. Any website that requires an online login may be targeted.

A single data breach can place many other accounts and organisations at risk. If a malicious cyber actor accesses a corporate network through a compromised account, such as one belonging to an employee or third-party contractor, they can then move through the network, learning about the system, establishing persistence in the network and stealing data. As access is gained using legitimate credentials, traditional security measures – such as anti-virus software and network intrusion detection systems – often fail to detect the activity.

Explainer 2: OAIC Notifiable Data Breaches scheme statistics

The Notifiable Data Breaches scheme requires organisations covered by the Privacy Act 1988 to notify the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) and affected individuals when a data breach involving personal information is likely to result in serious harm.

The OAIC regularly publishes statistical information on data breach notifications it receives to help organisations and the public understand and address privacy risks identified through the scheme.

The OAIC received 1,012 data breach notifications in the FY2023-24, a 13% increase compared to 2022–23. Of the data breaches notified to the OAIC, 41% (or 413 notifications), resulted from cyber security incidents. Of the 413 cyber security incidents:

- 60% involved compromised credentials

- 26% involved ransomware

Additionally, the OAIC was notified of breaches that resulted from hacking (8%) and malware (4%). Of note, cyber security incidents were the cause of the majority (69%) of large-scale breaches, defined as those affecting 5,000 or more Australians. This included three breaches that affected one million or more Australians.

The risk of outsourcing personal information handling to third parties continues to be a prevalent issue. In the FY2023–24, a high number of large-scale data breaches resulted from a compromise within a supply chain.

The human factor also poses a threat to the strength of an entity’s personal information security. Regardless of how secure an entity’s systems are, individuals commonly contribute, intentionally or inadvertently, to the occurrence of data breaches.

Further details on the Notifiable Data Breaches scheme are available on the OAIC website.

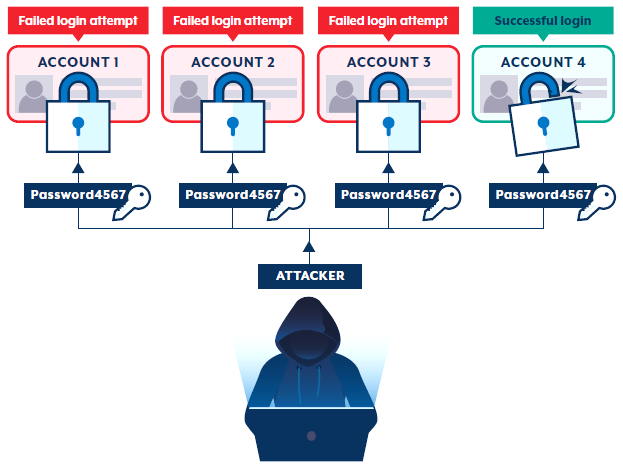

Password spraying as a high-volume attack tactic

Password spraying is a brute-force attack where malicious cyber actors attempt to access a large number of accounts with commonly used passwords. By trying a single password across several accounts, followed by another single password on the same accounts, malicious cyber actors can circumvent the common cyber security protocol of an account locking after a certain number of failed login attempts within a short period of time.

Password spraying in practice

When a malicious cyber actor wants to access an organisation’s email accounts, they begin by collating a large list of employee email addresses on the dark web, which were obtained through an earlier data breach the company is not yet aware of. Using automated tools, the actor attempts to log into several accounts using one common weak password. The actor repeats this process with different passwords, quickly moving down the list of email addresses. As the actor only attempts a couple of passwords per email address, they avoid detection by the organisation’s cyber security system. The actor continues to try different common passwords for each email address until they gain access.

Although simple, password spraying is a highly effective method of attack, able to target hundreds or even thousands of users simultaneously. Because actors can target many users at once, the likelihood of finding at least one or two accounts that use a common, weak password is high. Usually, it only takes access to a single account to provide entry into the broader network, making the organisation vulnerable to further exploitation.

Explainer 3: Scams and cyber-related threats – learnings from Scamwatch data

The line between cybercrime (cyber-dependent crimes) and scams (cyber-enabled crime) can blur when scammers use cyber-dependent techniques to commit a scam, such as where malware is used to facilitate a scam. An example of malware-facilitated scams is using adware – which causes splash screens to ‘pop-up’ on victims’ computers. In this example, the victim believes their device has been compromised and is prompted by the pop-up to call a phone number where a scammer impersonates reputable brands, advising of computer security issues. The scammer will then convince the victim to install remote access software on their device to provide full access to the cybercriminals.

There are five categories where cyber-related threats may be used to facilitate the scams. These are phishing, remote access scams, identity theft (account takeover), hacking, and ransomware and malware scams. It is rare for Scamwatch to receive reports involving true cyber-dependent crimes.

Most scams relate to cyber-enabled crimes, such as phishing. Phishing represents 55% of all losses and 74% of all reports across all five categories in FY2023–24. Together, there were just over 150,000 reports with over $33 million in losses for these scam types: 1% of these reports mentioned that money was stolen, while 8% mentioned that personal information was stolen.

Credential stuffing and password spraying are known as brute-force attacks. In FY2023–24, 8% of all cyber security incidents responded to by ASD included brute force-related activity. Organisations and individuals with poor cyber security practices, such as shared or repeated passwords, are more vulnerable to a brute-force attack, including by both credential stuffing and password spraying.

ASD recommends using multi-factor authentication (MFA) to defend against the majority of password-related cyber attacks, including credential stuffing and password spraying attacks. MFA requires a combination of two or more of the following factors to access your accounts:

- something you know (for example, a PIN or passphrase)

- something you have (for example, a physical token, authenticator application or email)

- something you are (for example, a fingerprint or facial recognition).

Quishing – the unseen threat in QR code technology

Quick Response (QR) phishing – known as quishing – is a type of phishing attack where cybercriminals use QR codes to trick people into providing personal information or downloading malware onto their smart device. The emergence and rapid expansion of QR codes make a convenient way for users to access information. QR codes are becoming commonplace and used more and more by businesses. For example, scanning QR codes to order from a menu in a local café, or to pay at a parking meter.

People have already placed their trust in this technology. However, the prevalence of QR codes in everyday life presents a potential threat to users, and the effectiveness of quishing attacks is enhanced when cybercriminals exploit this trust. Cybercriminals can embed malicious URLs into QR codes that, when scanned, link to a malicious website or prompt users to download files that can monitor their online activity, steal personal information or gain access to their device. In FY2023–24, ASD responded to 30 quishing-related incidents targeting Australian organisations, demonstrating that social engineering has taken on a new form.

Case study 10: MFA email scam

In late 2023, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) released a scam alert, warning of an increase in reports about an email scam impersonating the ATO. The email scam advised clients that due to an ATO security upgrade, they are required to update the MFA on their ATO account. The scam email included a QR code that linked to a fake myGov login page, designed to steal clients’ myGov account details.

Once a scammer has access to an individual’s myGov account, they may be able to make fraudulent lodgements and change bank details so that any payments are redirected to a scammer’s account.

Defending against and deterring cybercrime

Everyone must play a role in enhancing cyber security and reducing the risk of cybercrime. We encourage all Australians to:

- turn on MFA for accounts

- use long, unique passphrases for each account, especially if MFA is not available

- check automatic updates are on and install new updates as soon as possible

- back up important files and device settings regularly

- be alert for phishing messages and scams

- sign up for ASD free Alert Service

- report cybercrime, cyber security incidents and vulnerabilities through ReportCyber.

ASD also has several resources available to individuals, businesses and government to help improve cyber security, including:

Case study 11: ASD assists AISNSW in discovery of malware

To an onlooker, a not-for-profit organisation in the education sector would seem an unlikely target for cybercrime. However, malicious cyber actors frequently target the education sector, as the Association of Independent Schools of NSW (AISNSW) found out when they were alerted to malware lurking on their system.

AISNSW first became aware of the malware in November 2023 when ASD sent them a notification advising that Gootloader malware had been detected on one of their devices. Gootloader is an ‘Initial Access as a Service’ tool used to distribute other forms of malware.

The malware infected the system when an employee searched online for an Australian education sector enterprise agreement and clicked on a malicious sponsored link – a technique known as search engine optimisation (SEO) poisoning. This sent the employee to a honeypot website designed to look like an online forum. The employee downloaded a ZIP file purporting to be a copy of the enterprise agreement posted by a forum user. This executed the Gootloader payload.

The malicious cyber actor had persistent access to the network for three days. While the actor did not conduct command-and-control activities on the network, they may have been positioned to on-sell the access to another cybercriminal to use for ransomware or data theft.

Within two hours of receiving the notification from ASD, AISNSW’s ICT team had isolated the infected device and enacted controls to remediate the issue. Subsequently, the device was reimaged. In the following days, AISNSW worked with both ASD and the AFP, providing indicators of compromise (IOCs) to help prevent future compromises of other organisations.

It was through AISNSW’s membership of ASD’s Cyber Security Partnership Program that they were able to get timely advice directed to the right people within their organisation, expediting remediation. AISNSW has been a member of the ASD’s Cyber Security Partnership Program since March 2023. Since the compromise, AISNSW has been encouraging their contacts within the education sector to join the Partnership Program.

‘The ASD’s Cyber Security Partnership Program has proven invaluable to us in many ways, but in this instance it literally saved us from a potentially significant cyber incident,’ said Marcus Claxon, Manager: Cyber Security and Infrastructure Advisory Services at AISNSW.

‘It has also demonstrated the benefits of government and organisations working together in our cyber defence efforts.’

Case study 12: Operation ZINGER

The AFP’s Operation ZINGER is an investigation into Australian alleged offenders purchasing and using compromised Australian devices. Operation ZINGER is the AFP’s parallel investigation, with US Federal Bureau of Investigation’s ‘Operation Cookie Monster’, into the illicit online marketplace named Genesis Market.

Genesis Market was an invitation-only marketplace that sold login details, web-browsing cookies and other sensitive information stolen from compromised devices and computers around the world. Buyers could obtain access to banking and personal information – details that could be used to access government services.

A globally coordinated operation occurred in April 2023, involving the takedown of Genesis Market, with more than 100 people arrested as a result of more than 300 police actions across 17 countries.

In Australia, the AFP-led Joint Policing Cybercrime Coordination Centre coordinated the overt phase involving 27 search warrants across (and in conjunction with) multiple states and territories. The operation disrupted individuals alleged to be buying stolen personal information via Genesis Market in order to commit various fraud or cybercrime offences, including against financial institutions and government agencies. The AFP identified more than 36,000 compromised Australian devices available for sale on Genesis Market, part of approximately two million sets of credentials, including those containing details from myGov and Australian financial institutions.

Along with Australia, 17 other countries were involved in this operation: the US, the Netherlands, Spain, France, Finland, Germany, Italy, Poland, Romania, Sweden, Denmark, Canada, Switzerland, the UK, Iceland, New Zealand and Estonia.

To date, 12 alleged offenders have been arrested and charged in Australia with cybercrime offences.