AccuHealth’s kits consist of sensors and tablets that guide patients through biometric data collection (blood pressure, glucose levels, weight, and other indicators) and quick survey questions. The kits can be customized for different conditions (diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and even post acute care) and use on-market clinically validated devices.

Trained on deidentified records of 2.4 million Chilean patients,11 AccuHealth’s algorithm segments patients based on health trends and psychological and sociological profiles to identify high-risk patients. This enables health coaches to concentrate on those for whom the impact of monitoring is likely greatest, decreasing the cost and effort involved in managing populations.

To assess clinical impact, AccuHealth conducted a study of 4,000 diabetics using its solution and measured A1c blood sugar and blood pressure levels at study start-up, monthly, and after a year. Results showed a 1.5-point reduction in A1c from the sixth month onward. AccuHealth estimates this translates into a 20–40 percent decrease in medical complications for chronic patients and a 30 percent decrease in costs over the next 10 years.12

AccuHealth reports its solution has led to a 32 percent reduction in inpatient and 15 percent reduction in emergency visits in a payer’s population. Additionally, it has led to a 41 percent decrease in costs associated with medical leaves, a major expenditure for payers in Chile. On average, private payers see a 35 percent savings from the AccuHealth solution.13

AccuHealth runs five full-scale and 10 pilot programs across five provinces and intends to expand its reach to 100,000 Chileans in the medium to long term, by working with more public and private payers.

Interoperable data and platforms

In this section, we talk about how interoperable data and platforms allow for exchange of health information and analytics that help increase the speed and effectiveness of health interventions. The case studies fall under two categories:

- Systemwide platforms that serve as regional or national infrastructures for health data exchange and storage

- Technological solutions to support clinical initiatives at hospital systems

Systemwide digital health platforms. In the future, we expect data to flow seamlessly across platforms, creating new ways for consumers and care providers to proactively collaborate while supporting a system of wellness. Systemwide platforms are huge undertakings, particularly in view of numerous legacy systems that impede interoperability, and certain basic capabilities must be in place to create a foundation for data-sharing.

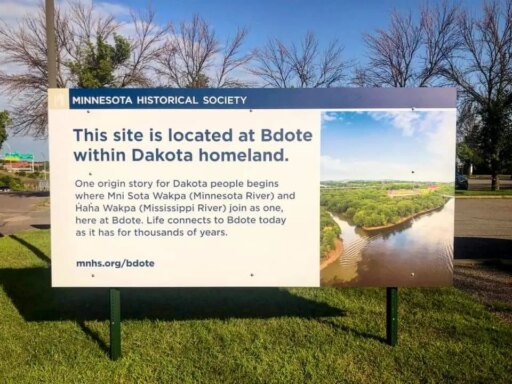

For instance, achieving interoperability requires changes in clinical documentation practices at the organization and user level, as well as complex interfaces among clinical IT systems, even when standards are in place. Building its e-health system from the ground up, before providers had a chance to invest in their own electronic systems, Estonia may have benefited from early adoption. Australia and the Netherlands represent a more typical scenario where multiple legacy systems, EHR platforms, and organization-specific conventions have evolved as barriers to interoperability. To support interoperability, all three countries have implemented a system of unique IDs for patients, providers, and organizations, as well as strict authentication rules.

Typically, a new legal and regulatory framework is required to support digital health efforts. The pace and scale of adoption often hinges on a national decision of opt-in or opt-out for consumers’ participation in data sharing. An opt-out approach has been shown to increase adoption. Estonia has adopted opt-out from the beginning, without much controversy. Australia’s move from opt-in to opt-out was a solid course correction that should lead to higher usage, whereas the Netherlands may see a decline in usage after switching to an opt-in model.14 To gain public and political support for opt-out, legal and technological safeguards of data privacy and security are necessary. All three countries have incorporated these safeguards. Before connecting to a national network, providers must demonstrate that their IT systems meet technical and security requirements. Consumers can authorize and restrict access for certain providers, restrict access to portions of the record, and close the record altogether. The systems generate access logs, so consumers know who viewed or contributed to their record.

As is often the case with technology, an if you build it, they will come approach is unlikely to materialize. Achieving a critical mass of users is a common challenge. With providers, incentives and regulatory mandates are common approaches, whereas with consumers, opt-out is a good first step. Ongoing public awareness campaigns serve as reinforcement. But most importantly, technology should deliver value to users; this ensures not just nominal adoption, but actual use.

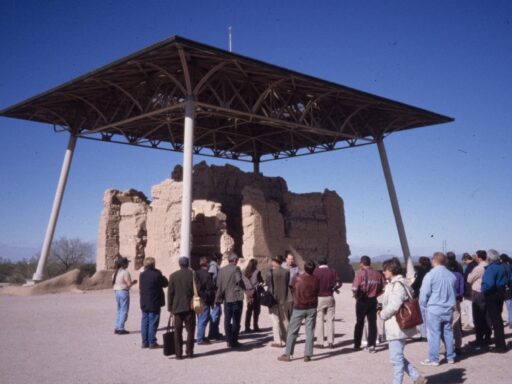

Estonia: Early adopter of e-health

E-health as part of a broader e-government strategy can deliver cost-effective solutions

Known worldwide for its e-government services in tax, voting, health care, education, and public safety,15 Estonia began to develop e-health infrastructure in the early 2000s and introduced the first e-health services for consumers in 2008.16