The Student Orientation Advising and Registration workshop at Long Beach State felt like a staged play.

It began with an open door to opportunity, and ended with a police report and many unanswered questions.

I remember my skin dampening under a restless July sun, an ache in my shoulder beneath an overweight bag, begging for refuge in the Liberal Arts 5 building restroom.

Out of the many experiences that day, being the victim of a voyeurism crime was the last one I expected.

The incident replays like an act in my head. The light steps trailing behind me, an uneasy silence outside the stall. I was followed into the women’s restroom and recorded with a cellphone from beneath the stall.

The intruder was gone in an instant, as if it had never happened.

I reported the incident to the University Police Department, but the only recollection I had of the intruder’s appearance was a pair of sneakers. I was relying completely on the police department’s investigation.

I remember a numbness gnawing at my initial shock as the officer at the scene told me that some of the cameras in the area may not have been working. He said I would receive a call if there were any updates.

That was the last I would hear from the investigation.

The search for evidence was halted by UPD’s outdated reporting procedures and limited public data. As records requests were met with policy restrictions, it was clear that there is room to improve victim support services at CSULB.

The frequency of related crimes on campus could be linked to the operational condition of security cameras. There was a possibility that crime investigations would continue to be halted or remain unresolved for other victims.

Through the looking glass: campus surveillance

The Current’s staff reached out to Beach Building Services about the functionality of campus cameras and was redirected to campus police.

Lieutenant Johnny Leyva said security cameras are generally a valuable tool used for investigations.

“If I learned that any camera is temporarily offline, we do make every effort to address it, to find out what’s going on and to resolve that problem too,” Leyva said.

University Police Chief John Brockie said as a matter of practice and safety, UPD does not publicize the locations of cameras or their operational condition.

Since the department couldn’t disclose information on camera operations, The Current requested reports on the surveillance budgets and maintenance records through the university.

As UPD operates in a separate division represented by the CSULB cabinet, Jamarr Johnson, director of public records at CSULB, said the school does not hold responsive contracts used by the police department.

Johnson forwarded a link to the CSU systemwide police department policies. The policies include the department’s general operations and procedures, but do not contain security camera maintenance logs.

Johnson also provided the CSULB security camera policy, but there was no summary data to indicate how often security cameras are used during investigations.

According to the policy, UPD may approve a written request by the president, vice presidents or administrators responsible for overseeing police, human resources officials and other certified faculty members to review camera footage data.

A different approach

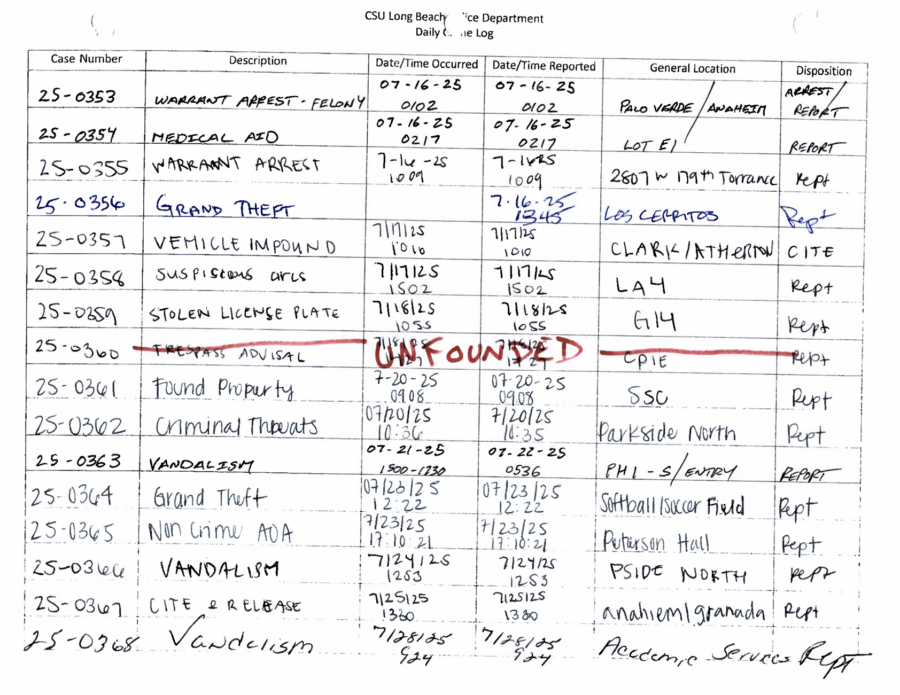

A California Public Records request for a list of similar reports from the most recent five years and the arrest logs tied to the offenses listed was met with numerous scanned copies of UPD’s handwritten daily crime log.

Johnson said the police department was unable to filter out the specific incidents because there were no electronic daily crime logs.

The scanned logs contained every crime reported from 2020 to 2025—over 30 pages per year.

According to Chief Brockie, the previous electronic log experienced several crashes within the software interface and UPD defaulted to the handwritten log instead.

“I haven’t seen a software product that does it correctly,” Brockie said. “I’ve looked at other ones, and it’s twice as much as what we spend right now for that software.”

Other CSU campuses, such as Cal State Northridge, Cal Poly Pomona, Cal State Fullerton and Cal State San Bernardino, have electronic daily crime logs available to the public online. CSULB has a record identifier chart listed online, but no electronic crime log.

Scan of daily crime logs filled out by university police. Monica Garcia | Long Beach Current

In the logs received, it was unclear whether other reports were similar to mine, since the description on my report said “suspicious circs.” Four other incidents noting “suspicious circs” were reported between June and July 2025.

According to Brockie, this stands for suspicious circumstances, noted in the log for brevity. Brockie said my particular case should have been updated with a specific code, but it wasn’t until later.

According to the Jeanne Clery Campus Security Act, new information and dispositions to cases must be updated on the log no later than two business days after they become available.

“The dispatcher didn’t know the specific section at the time … They’re not expected to look up a crime code and go, ‘OK, well, it sounds like it might be this, so I’m going to look up a crime code for it,’” Brockie said.

As part of UPD practice, dispatchers use a computer-aided dispatch system to determine a response upon receiving a call. The officer at the scene then provides more information into UPD’s records management system, separate from the dispatcher system.

“So then the report was written, the correct heading was in the records management system, and it didn’t get converted over,” Brockie said.

In addition to the scanned logs provided by UPD, there was no information on the arrests related to the offenses requested.

How does CSULB rank in its Title IX support services?

Master of Fine Arts researcher Andrea Perez at Cal State University, Sacramento, conducted a statistical examination in 2024 to compare sexual assault and violence statistics in the CSU system.

Perez reviewed Title IX webpages for all 23 CSUs and the availability of resources to victims of related crimes.

Overall, CSULB received 26 out of 40 potential points on the rubric for Title IX webpage support services.

Perez ranked the universities’ Title IX webpages based on 10 questions, each with a score range of one (poor) to four (very good).

The rubric was used to detect absent information that would hinder a victim’s likelihood to report abuse, such as a lack of counseling service information in the Title IX pages.

CSULB received a “good” score for having accessible information on how to file a report on its Title IX page.

It ranked “poor” in the webpage’s accessibility to procedures following a report of sexual harassment or assault. This score indicated that the university did not provide information on what would happen after a student filed a report.

Open investigations

At the time of publication, there have been no updates to the report filed during the SOAR workshop at CSULB. There is no public information regarding the functionality of security cameras or their maintenance records.

Chief Brockie said California’s Public Records Act has limitations on obtaining electronic crime reports for investigative purposes, including UPD’s records management system.

“The daily crime log is always available,” Brockie said. “The Public Records Act doesn’t require an agency to create documents.”

Whether it be faulty security cameras or outdated reporting systems, student support services could benefit from a redirection of funds within the campus police department.

Given that other CSU campuses have provided the public with the means to filter electronic daily crime logs, CSULB may be sitting on the sidelines of open investigations while victims seek answers.