The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) released an updated version of its Artificial Intelligence (AI) Use Case Inventory this summer. At first glance, the changes seemed routine—some AI software programs were marked “inactive,” and a new one was added. But upon closer examination, the removal of the AI use cases does not appear to indicate a retreat from—but an expansion of—those AI capabilities.

Taken alongside reporting from The Guardian and Wired, the update points to broader trends in immigration enforcement: deploying similar AI functions within larger vendor-run platforms and expanding into continuous surveillance systems that pull in and analyze far more information than before.

Two months earlier, in May, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) reported using 23 active AI software programs for immigration enforcement. By July, four of those had become “inactive,” and one—Email Analytics for Investigative Data—was moved back to “implementation and assessment” phase for reconfiguration under a new system. At face value, this looks like a pullback in AI programs. However, recent reports show there is more going on. Many similar features are part of larger AI software platforms that generate automated decisions that are harder to oversee.

Program changes made to the DHS AI inventory include:

- Email Analytics for Investigative Data: Active (returned to reassessment). Automates sorting, translation, and entity extraction from seized emails.

- Mobile Device Analytics for Investigative Data: Inactive. Parsed data from seized phones and devices.

- Identification Card & Travel Doc Code Detection: Inactive. Used computer vision to scan IDs.

- Voice Analytics for Investigative Data: Inactive. Transcribed and translated audio.

- Video Analysis Tool (VAT): Inactive. Flagged faces and video snippets.

DHS also discontinued its use of three commercial generative AI services (for code, images, and chatbots) and added one new pilot program: the LIGER GenAI Toolkit, designed to support federal workers with tasks like drafting contracts and summarizing documents.

From specialized programs to big data platforms

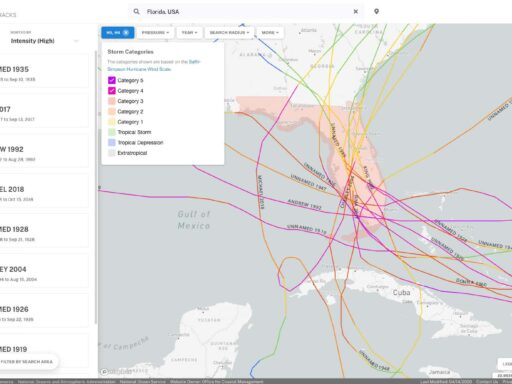

The DHS AI Use Case inventory lists programs as separate entries, but in practice, these programs rarely operate in isolation. Investigations by The Guardian, Wired, and NPR reveal that ICE increasingly relies on large vendor-built platforms—such as Palantir’s comprehensive immigration systems, Clearview AI’s facial-recognition tools, BI2’s iris-scanning devices, and Paragon’s phone-hacking software—that pull together many different forms of data and analysis in one place.

Palantir’s platforms, for example, have been used by ICE to analyze driver’s license scans, extract information from seized phones, cross-search location data, and link records from federal, state, and commercial databases. Wired reported that these tools combine social media posts, travel records, tax data, and phone extractions into unified investigative files. NPR also documented the use of mobile facial-recognition apps and iris scanners in field operations.

Considering these new ICE contracts, the underlying functions of DHS’s “inactive” AI programs—ID scanning, mobile device analytics, video analysis, audio transcription—clearly persist across newer contracts and technologies. ID scanning now appears in field apps like Mobile Fortify; mobile device analytics continue through tools from Cellebrite and Paragon; voice, video, and text analysis feed into social-media and communication-monitoring platforms from Zignal Labs and PenLink.

Such integration carries troubling risks. When dozens of discrete tools are fused into a single “black box,” oversight becomes harder. As functions consolidate in one large system, it becomes increasingly unclear how someone was identified and harder for any watchdog to trace the steps behind a decision. What data is used? How is it weighted? What errors or biases carry forward? Without transparency, accountability diffuses.

Ultimately, AI-driven outputs begin to shape enforcement decisions in ways that are difficult to challenge. As the system grows more opaque, enforcement decisions end up driven by the final output rather than any understandable process.

Vendor platforms and the new surveillance pipeline

Following a wave of vendor-built AI programs, ICE’s next moves show expansion. Procurement documents uncovered by Wired reveal that ICE plans to hire nearly 30 contractors to monitor social media platforms—Facebook, TikTok, Instagram, YouTube—around the clock. Analysts would turn posts, photos, and profiles into enforcement “leads” for ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations Division. ICE asked the contractors to indicate how they would integrate AI into their work, and the analysts would be equipped with the latest surveillance tools.

This marks a shift from static software programs designed to log data to continuous, real-time surveillance of everyday online life. As noted in a previous Council blog on Palantir’s ImmigrationOS, ICE is increasingly relying on vendor-built systems that combine case management, biometrics, link analysis, and surveillance tools into a single environment.

When viewed alongside this trend, the July AI inventory update looks less like a reduction in DHS’s use of AI and more like a reorganization. Programs marked “inactive” on paper are not disappearing; similar functions continue in larger, always-on systems. This update enables continuous, AI-assisted surveillance pipelines—systems that automate monitoring, sift through social and digital data, and surface “high-priority” individuals for enforcement.

Together, these developments reveal the same concern: so-called neutral or “technical” systems are, in fact, the products of policy choices. Algorithm design decisions—what data to ingest, how to categorize risk, when to flag someone—shape who gets targeted, detained, or deported. Treating these platforms as neutral obscures the fact that they are political technologies, crafted by people and influenced by institutional priorities.

The July DHS AI Use Case Inventory may look like a shuffle of line items, but it signals deeper shifts in immigration enforcement. Individual programs might have been deactivated on paper, but their capabilities live on inside the platforms of vendors like Palantir. At the same time, ICE is expanding its reach into continuous, real-time surveillance of individuals’ online lives. Addressing these risks requires strong safeguards: independent audits, clear public reporting on vendor systems, and robust Congressional oversight to ensure accountability.