eWOM and impulse buying

Research on impulse buying in social science began in the 1950s; the construct was associated with unplanned buying. The early study mainly investigated purchase decisions made by consumers after entering a retail store (Silvera et al. 2008). The impulse behavior research extended to exploring people’s reactions to the stimuli that markedly heighten emotional reactions (Iyer et al. 2020; Kim and Johnson 2016). Meanwhile, eWOM, engaged in spreading positive or negative service experiences (Zhang, Omran et al. 2021; Wakefield and Wakefield 2018), is a disseminating means in marketing and must be considered an essential topic in the online shopping era (Ahmad et al. 2022). Over the past decades, researchers have examined the pros and cons of eWOM in online shopping on short- and long-term judgments, as well as the influences of consumers’ product involvement and purchase experiences on the decisions (e.g., Abbasi et al. 2023; Ahmad et al. 2022; Hu and Kim 2018; Kim and Johnson 2016; Lee et al. 2022).

Tsao and Hsieh (2015) found that eWOM, transmitted by experts, celebrities, and other shoppers, can be more trusted than the stimuli from marketers. As a result, most consumers are accustomed to browsing reviews from other online users or internet celebrities before shopping online. Although opposing ratings are more potent in the marginal decrease of sales than positive ones are in the additional increase of sales (Chevalier and Mayzlin 2006; Verma and Dewani 2021), favorable consumers with self-enhancement and enjoyment are likelier to send recommendations that lead to impulse purchasing (Hu and Kim 2018; Kim and Johnson 2016). Furthermore, the argument quality of online reviews, characterized by perceived informativeness and persuasiveness, source credibility, and the number of reviews, significantly affects consumers’ purchase intention (Zhang et al. 2018).

In brief, the argument quality of online reviews, characterized by perceived informativeness, persuasiveness, and credibility, can affect consumers’ purchase intention. Those recommendations cause self-control failure (e.g., conflicting goals and standards, failure to keep track, or depletion of self-regulatory resources), which leads to impulsive purchases (Baumeister 2002; Lamberton 2020; Zhang et al. 2018). This occurrence is widespread in online shopping; therefore, the above discussion led us to form the following hypothesis:

H1: Positive eWOM contributes to impulse buying.

Consumer inertia in the impulse-control intervention

However, positive eWOM growth is also critical for consumers to resume reflective self-control, associated with re-examining the negative side of the established belief systems (Chevalier and Mayzlin 2006; Lamberton 2020; Vafeas and Hughes 2021). Consumer inertia as a risk-reduction strategy will likely retake charge in this appraisal transformation to cope with the rise of favorable reviews or ratings while embracing a new belief system (Chevalier and Mayzlin 2006; Kuo et al. 2013; Shiu 2021).

In management literature, inertia is defined as “rigid behavior and a reliance on past responses” (Vafeas and Hughes 2021). The construct can be conceptualized as having cognitive, affective, and behavioral aspects (Polites and Karahanna 2012). According to Kuppens et al. (2010), affective inertia is the degree to which a previous emotion can predict a person’s current emotional status, and it is defined as an emotional change brought on by pressure. In contrast, cognitive inertia consumes one’s mental resources in choosing options (Bruyneel et al. 2006). The third type, behavioral inertia, is what individuals always do without overthinking (Messner and Vosgerau 2010). The three types, taken together, demonstrate the propensity of consumers to stick to the habits or actions they adopt to respond rationally or irrationally (Anderson and Srinivasan 2003; Polites and Karahanna 2012; Shiu 2021; Shiu and Tzeng 2018).

A primary question is whether consumers can satisfy their needs using heuristic shortcuts in impulse control. This phenomenon relies on a particular condition when trading risks for benefits possibly invites bad long-term outcomes or as an alternative when self-control against impulsive purchases is vital for more rewarding ones (Reyna and Farley 2006). In light of this, consumer inertia is believed to be crucial for impulse-control intervention. The following hypotheses about the mediating roles of three dimensions of consumer inertia as risk-reduction strategies were thus developed for the transition from positive eWOM to impulse buying:

H2: Three types of consumer inertia mediate the relationship between positive eWOM and impulse buying (i.e., H2a: affective inertia, H2b: cognitive inertia, H2c: behavioral inertia).

The reciprocal influences among three types of consumer inertia

Previous relevant studies have investigated e-commerce adoption, focusing on users’ psychological influences (e.g., motivation, personality, and perception) (Al-Adwan et al. 2022). With that focus, flow theory posits that complete engagement in an intrinsically rewarding activity can elicit optimal experience through the presence of consumers’ cognitive and affective states (Csikszentmihalyi 2020; Ming et al. 2021). Individuals tend first to recall items linked together in their memory of cognition and affection in decision-making. When positive reinforcement is most continuously activated, the habitual use of the belief system will emerge from the genuine subconscious. As a result, behavioral inertia represents a consistent repurchasing or re-patronizing behavior for select products/services due to perceived transition costs or psychological commitment (Anderson and Srinivasan 2003; Huang and Yu 1999; Polites and Karahanna 2012; Seth et al. 2020). According to the above discussion, ongoing affective and cognitive stimulation is what leads to behavioral inertia. Thus, we put forth the following hypotheses:

H3: Behavioral inertia mediates the relationship between affective inertia and impulse buying.

H4: Behavioral inertia mediates the relationship between cognitive inertia and impulse buying.

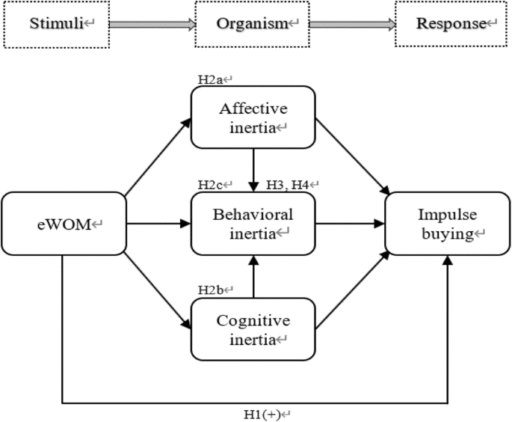

Research model

The hypothesized model we developed from the extant psychological research is illustrated in Fig. 1. The research model integrated the flow theory into a S-O-R framework (Ming et al. 2021; Shiu et al. 2023). Considering the cognitive load of rising reviews or ratings, this study aimed to examine whether a stimulus, such as positive eWOM, affects the flow experience that can trigger the intrinsic states of organisms, including three types of consumer inertia, leading to a response, such as impulse buying. The investigation focused on the direct impact of positive eWOM on impulse buying and the indirect effect of impulse control by including three mediators in this relationship (i.e., affective, cognitive, and behavioral inertia). Moreover, two additional mediating effects of behavioral inertia in the relationships between cognitive inertia and impulse buying and between affective inertia and impulse buying were tested since the behavioral habit likely stems from mental awareness and psychological emotion. Finally, the integrated model was built to evaluate consumers’ use of inertia as a risk-reduction/facilitating strategy that explains the transition from positive eWOM to impulse buying in an online shopping frenzy. Table 1 exhibits the most relevant studies supporting the integrated model and each hypothesis.

The research model integrated flow theory into a S-O-R framework. The study looked at how a stimulus—in this case, positive eWOM—affects the sensation of flow, which can cause three different types of consumer inertia and, ultimately, a response—in this case, impulse buying—by evoking the intrinsic states of an organism.